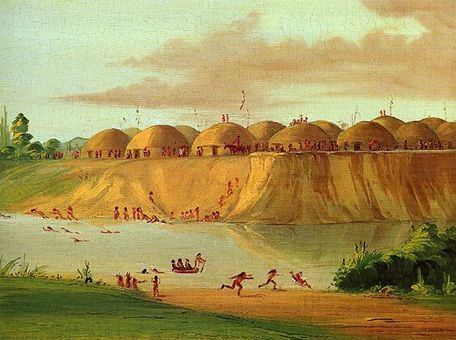

Mandan village on the Missouri River

Mandan village on the Missouri River But there are a thousand articles about the pipeline and the jobs it will or won’t create and whether it’s a good idea or a bad idea. I encourage everyone to read them carefully. The question I want to delve into here is one that doesn’t get a lot of direct attention:

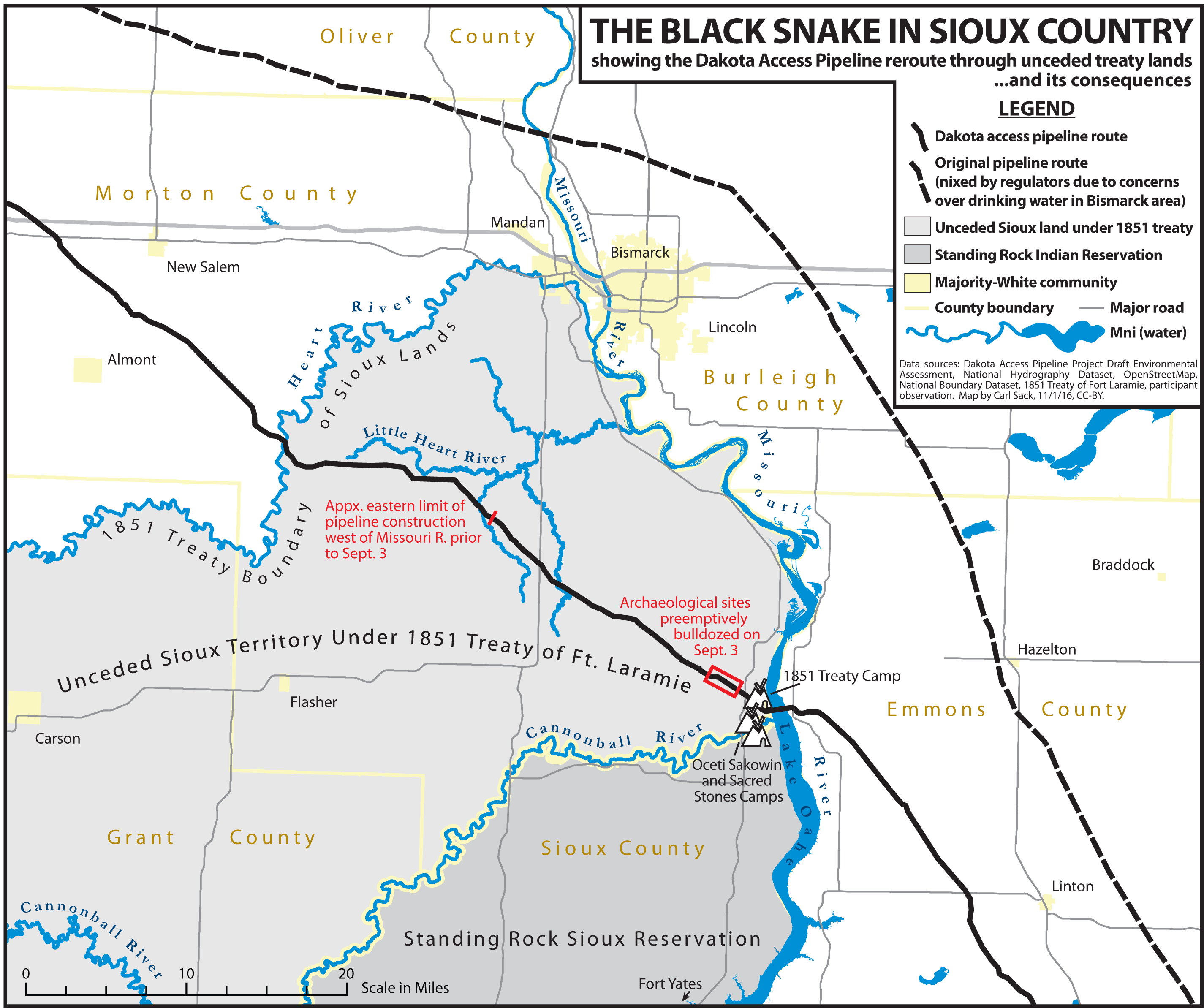

“Whose land is the proposed pipeline on?”

The pro-Water Protector articles will say that the Native Americans and their allies are protecting “their sacred land” while the pro-pipeline articles and social media commentary will say, “those protesters are on private land that the pipeline was given permission to use so they (the Native Americans) need to move off.”

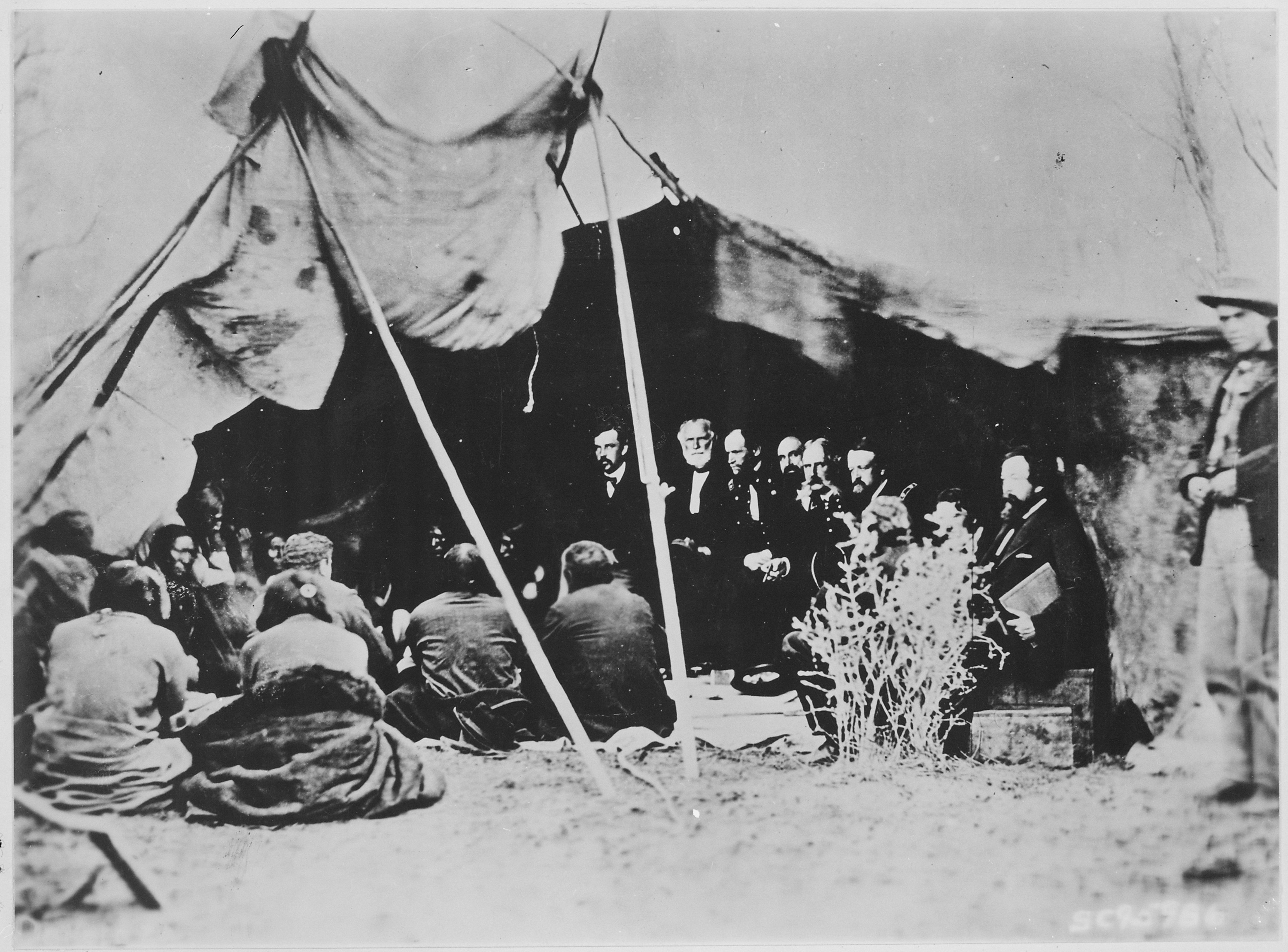

In April, 2016 a small encampment of indigenous youth began on the banks of the Missouri River on disputed land. Young people—native and non-native alike—ran a 500-mile spiritual relay from Cannonball, North Dakota to the district office of the United States Army Corps of Engineers in Omaha, Nebraska to deliver-- in person-- a unified statement of resistance against the construction of the pipeline and a petition that called for a full-scale environmental impact survey. The Army Corps declined. In July, ACOE issued the majority of the permits that were required for the construction of the entire pipeline project and construction began in all four states.

The Standing Rock Sioux immediately filed an injunction against the Army Corps, asking for further environmental impact study and archeological assessment. DAPL responded by issuing a 48 hour notification of their intent to begin drilling at Lake Oahe, despite lacking the permits for that particular bit of construction.

On August 6th, a second group of 30 native youth ran 2,000 miles, from North Dakota to Washington DC, to call upon the Obama Administration to require an independent full-scale environmental impact assessment for the Dakota Access Pipeline. They carried with them 140,000 signatures from supporters. At this point, three federal agencies, the Department of the Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Advisory Council on Historical Preservation, had all joined in the call for the assessment. The Army Corp again declined.

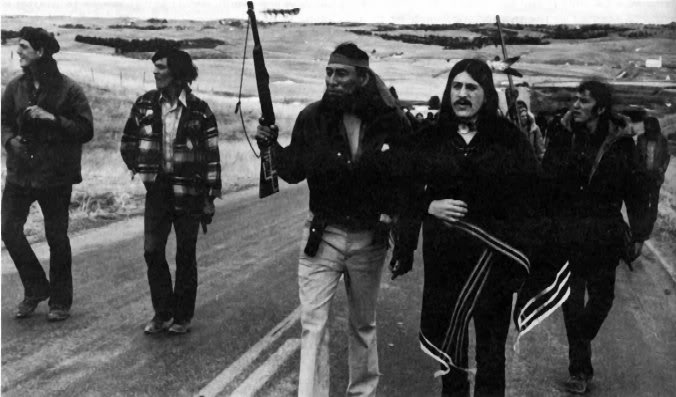

On August 8, 2016, Dakota Access, LLC. gave the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe a 48-hour notice that construction would begin. In response, several hundred protesters gathered including the Standing Rock tribe, their fellow tribes, and a coalition of allies ranging from farmers and ranchers to environmentalists. Over several months, they set up an encampment, known as the Sacred Stone Camp, just outside the construction site.

Though several people were arrested during this action, construction was successfully suspended while the developers filed a lawsuit requesting payment for alleged damages and restraining orders against the notably peaceful protesters. Eventually construction continued and so did the Sacred Stone Camp. We’ve all seen photos showing lines of heavily militarized cops standing between construction workers and protectors, some of whom rode on horseback wearing their tribe’s traditional garb.

Among those arrested first was Standing Rock Chairman Dave Archambault II who had this to say of the pipeline, or “black snake” as many indigenous people call it:

“We don’t want this black snake within our Treaty boundaries. We need to stop this pipeline that threatens our water. We have said repeatedly we don’t want it here. We want the Army Corps of Engineers to honor the same rights and protections that were afforded to others, rights we were never afforded when it comes to our territories. We demand the pipeline be stopped and kept off our Treaty boundaries…We have a voice, and we are here using it collectively in a respectful and peaceful manner, The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is doing everything it can legally, through advocacy and by speaking directly to the powers that be who could have helped us before construction began. This has happened over and over, and we will not continue to be completely ignored and let the Army Corps of Engineers ride roughshod over our rights…We have a serious obligation, a core responsibility to our people and to our children, to protect our source of water. Our people will receive no benefits from this pipeline, yet we are paying the ultimate price for it with our water. We will not stop asking the federal government and Army Corps to end their attacks on our water and our people.” |

To even scratch the surface on that question, we have to go back a few hundred years and then settle in the mid 1800’s. I’m going to borrow, steal, condense, and edit heavily from a great short-form timeline entitled “The Federal Government and the Lakota Sioux” and intersperse a few important details from a wonderful longer version historical archives of the state of North Dakota. I encourage all to read the longer history for full context. In this next section is another short version of hundreds of years of history between the US Government and the Dakota, Lakota, and other tribes within the Great Sioux Nation.

The influx of French traders changed the lives of the tribes they encountered. The first recorded encounter between the Sioux and the French occurred when Radisson and Groseilliers reached what is now Wisconsin during the winter of 1659–60. The Sioux people allied there in what was known as the Seven Council Fires or Oceti Sakowin. [You might have seen this same term used in several recent articles naming the current large encampments after the fact that it is a very rare congregation of the Seven Fires Council that has not happened since around 1850.] This Seven Council Fire was reportedly comprised of the Santee division (Dakota speakers) with four groups, the Middle division (Nakota speakers) with two groups, and the Teton or Western division (Lakota speakers) originally consisting of one group. In the Woodland region the people’s economy was based on fishing, hunting, gathering, and some cultivation of corn. In the 1600’s the Sioux were pushed westward by other tribes who obtained guns through the French fur trade.

By 1750 the Middle Sioux were settled along the Missouri River while the Teton pushed farther west into the Black Hills and beyond to present-day states as Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana. Essentially, the tribes were forced out of one homeland due to European expansion. But the Sioux showed great adaptability.

Both the Dakota and Lakota relied almost exclusively on the buffalo as a major source of food, shelter, and material items. Both groups had complex spiritual ceremonies, and placed much emphasis on family with cultural values that benefitted the tribe rather than the individual; these cultural and spiritual values remain important among many tribal peoples to the present day. Once the Dakota and Lakota acquired the horse, in the mid 1700s, there was an impact on the material culture and social customs. Tepees became larger, there was greater mobility, and hunting became more productive. Additionally, the horse had a direct impact on the integration of warfare into the fabric of tribal life. It is important to understand the main object of Plains Indian warfare was never to acquire land or to control another group of people. Plains Indian warfare focused on raiding other tribes’ camps for horses and acquiring honors connected with capturing horses. In these raids, very much like contests, men sought to out-smart the enemy and gain individual honors by counting coup, or striking the enemy with the hand or a special staff. Plains warfare emphasized out-smarting the enemy, not killing them. With the advent of the horse onto the Plains, warfare traditions became institutionalized among tribes. This style of warfare, described by one author as comparable to a rough game of football, changed dramatically after encounters with the U.S. Army in the 1850s.

These lifeways and warfare customs were followed throughout the larger Dakota / Lakota “Sioux” region for about 200 years until the discovery of gold in California in 1849. Up until this time the U.S. government considered the west a “permanent Indian frontier”—an inhospitable land with little economic value inhabited by Indians. In the early 1850s, overland travelers who were en route to gold fields began to cross through Lakota territory. However, the discovery of mineral wealth in the west caused the U.S. to extend its boundaries to the Pacific Ocean, encroaching on the Indian lands and threatening the buffalo herds. This in turn set off a series of confrontations between whites and Indians of the trans-Mississippi West. Fortune seekers moving along the Platte River Road cut right through traditional Lakota territory and although generally left alone, the white travelers were frightened by the turmoil and commotion caused by the intertribal raids and they demanded government protection.

1852 U.S. government violated the 1851 treaty. The U.S. Senate decreased the annual payment of $50,000 to the Sioux people from 50 years to 10 years.

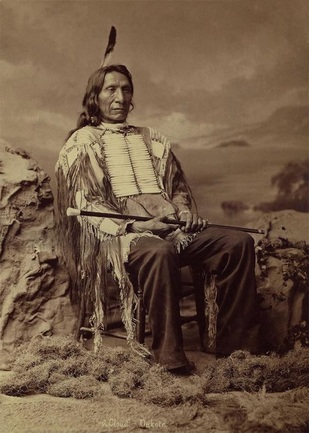

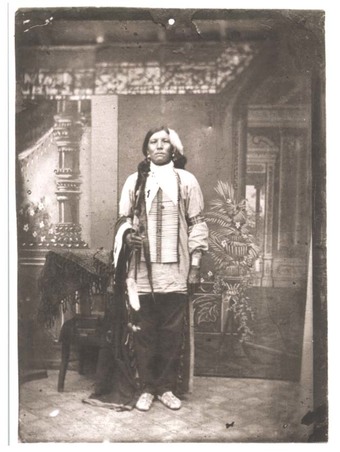

Red Cloud or Scarlet-Cloud aka Makhpiya-luta-or-Ma-kpe-ah-lou-tah_Oglala Sioux is seen here in 1880. (FirstPeople.us)

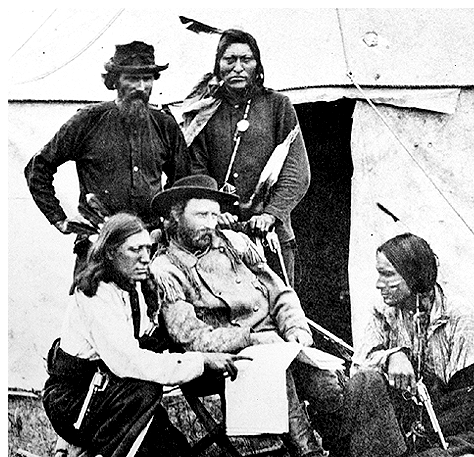

Red Cloud or Scarlet-Cloud aka Makhpiya-luta-or-Ma-kpe-ah-lou-tah_Oglala Sioux is seen here in 1880. (FirstPeople.us) Thus began the Powder River War (aka Red Cloud's War) as the Lakotas and their Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho allies fought the U.S. Army at the various forts in Lakota territory. Those Sioux friendly to the U.S. government, however, signed a treaty giving Euro-Americans the right to use the Bozeman Trail in return for guns and ammuition. Soon thereafter, the U.S. Army began building more forts along the Trail.

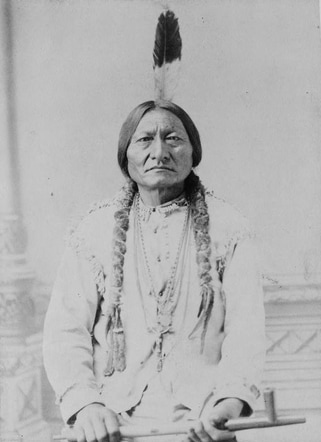

At the Grand Council of 6,000 tribes at Bear Butte, the sacred mountain of the Cheyenne, Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, and Sitting Bull, among other great leaders, pledged to end further encroachment of Sioux territory by the whites.

Following the Civil War, after deadly European diseases and hundreds of wars with the white man had already wiped out untold numbers of Native Americans, the U.S. government had ratified nearly 400 treaties with the Plains Indians. But as the Gold Rush, the pressures of Manifest Destiny, and land grants for railroad construction led to greater expansion in the West, the majority of these treaties were broken. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s first postwar command covered the territory west of the Mississippi and east of the Rocky Mountains, and his top priority was to protect the construction of the railroads. In 1867, he wrote to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, “we are not going to let thieving, ragged Indians check and stop the progress” of the railroads.

Rather than addressing the issue of trespass in Sioux country, the government responded with talk of yet another treaty with the Sioux.

1868 Fort Laramie Treaty brought peace between the Sioux and the US government by guaranteeing that the Sioux had "absolute and undisturbed use of the Great Sioux Reservation...No persons...shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in territory described in this article, or without consent of the Indians...No treaty for the cession of any portion or part of the reservation herein described...shall be of any validity or force...unless executed and signed by at least three-fourth of all adult male Indians, occupying or interested in the same." This treaty proved to be one of the most controversial in the history of US-Indian relations - it ended the war between the Sioux and the U.S. government, split the Oglala nation into those "friendlies" willing to work with the U.S. government and the "hostiles" with whom the U.S. banned trade, and set the legal stage for Sioux claims to the Black Hills that continue into the 21st Century.

[I’m sure most readers can see where this is going. But it’s worth stating that these people had already migrated across the county and adapted their culture to a new way of life. And this wasn’t just a land deal, the migration of Europeans brought with them an existential crisis. Red Cloud wasn’t the only one to notice that the white men never seemed satisfied. No concession was enough for the white men. They made promises and then didn’t keep them. If they couldn’t uphold the original Fort Laramie Treaty, then why would they keep their word about anything else?

Continue reading and you’ll see how interconnected the past is to later events and even to what’s going on today.

But how was this 1868 Treaty different from the 1851 treaty?]

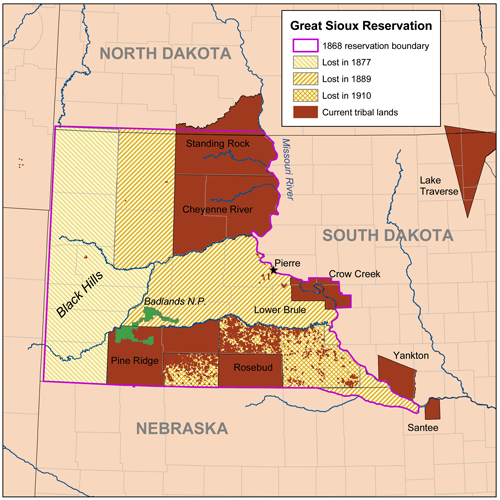

- Set aside a 25 million acre tract of land for the Lakota and Dakota (down from 134 million acres from the previous treaty) encompassing all the land in South Dakota west of the Missouri River, to be known as the Great Sioux Reservation;

- Permit the Dakota and Lakota to hunt in areas of Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota until the buffalo were gone;

- Provide for an agency, grist mill, and schools to be located on the Great Sioux Reservation;

- Provide for land allotments to be made to individual Indians; and provide clothing, blankets, and rations of food to be distributed to all Dakotas and Lakotas living within the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation.

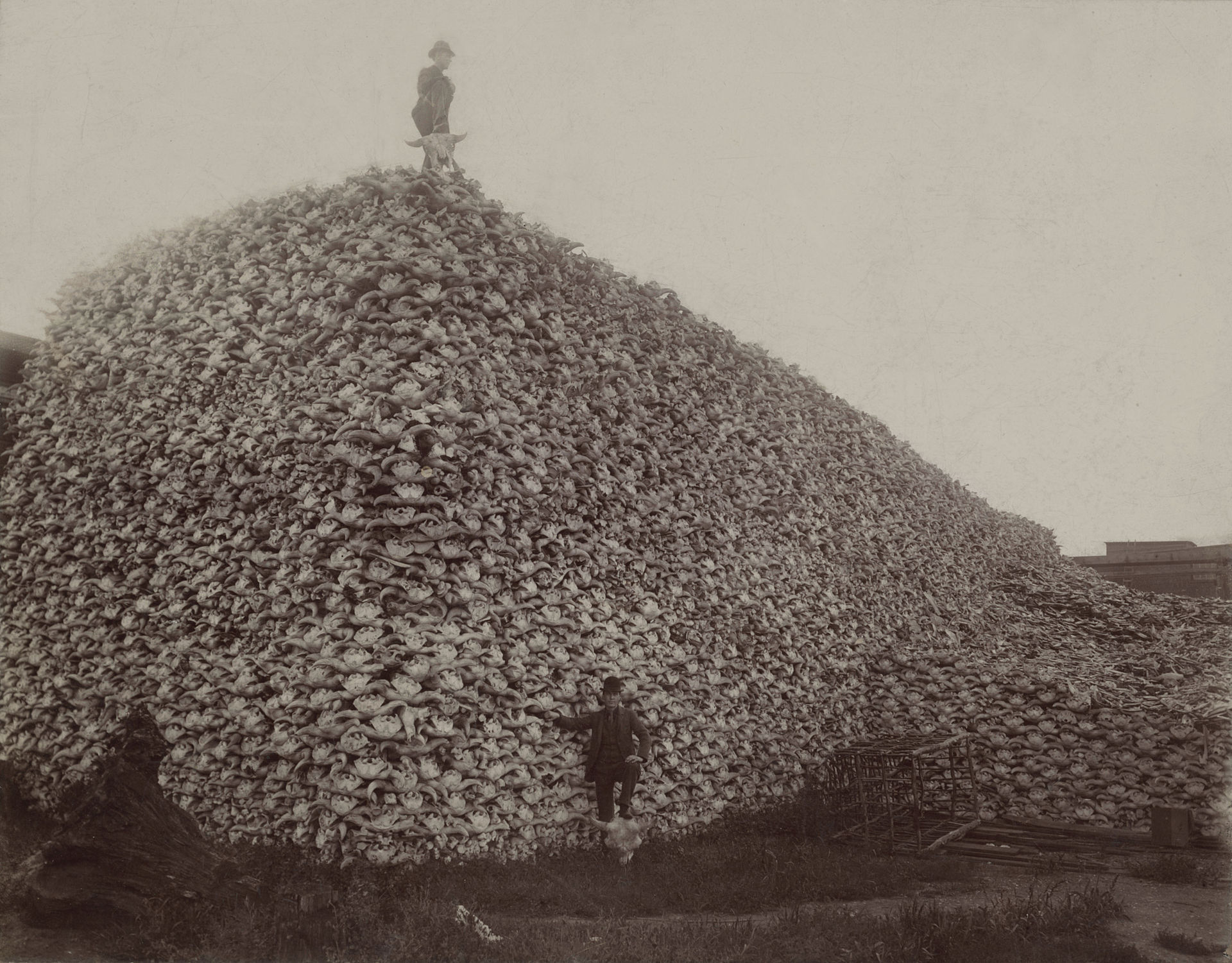

Buffalo Slaughter as weapon of containment

On June 26, 1869, the Army Navy Journal reported: "General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins." [17] According to Professor David Smits: "Frustrated bluecoats, unable to deliver a punishing blow to the so-called "Hostiles,"unless they were immobilized in their winter camps, could, however, strike at a more accessible target, namely, the buffalo.That tactic also made curious sense, for in soldiers' minds the buffalo and the Plains Indian were virtually inseparable."

Trains and repeat fire rifles made buffalo slaughter easier than at any other time in history. The U.S. military strategically exterminated bison in masses. By ridding the Plains Indians of their primary food source, they would become further dependent on reservations for subsistence. Bison meat also supplemented the army rations, and commanders issued hunting passes freely to their troops to obtain fresh meat. Oftentimes military men would kill the bison and not take any of the meat from it. As Kiowa chief Santanta complained at the Medicine Lodge Treaty Council of 1867: "has the white man become a child, that he should recklessly kill and not eat? When the red men slay game, they do so that they may live and not starve."[17] By 1893, fewer than 400 wild bison were left—and Native Americans were pushed to reservations, relying on farming and waiting on scanty government rations for food.

On December 3, 1875, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs required that all Sioux people report to their agency by January 31, 1876 for a head count. http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/resources/archives/six/bighorn.htm

1876 On February 7, the War Department authorized General Sheridan to move into Indian lands and round up the "hostile Sioux" who had not reported to their agency. The first attack happened on March 17 - sooner than the Sioux were expecting - thus escalating hostilities that culminated in the Battle of Little Big Horn on June 25 - also known as Custer's Last Stand. The battle occurred after General Custer and the 7th Calvary of about 600 soldiers split into three battalions, surrounded and attacked a Sioux camp.

Custer and all his men were killed in what was the largest defeat ever of a U.S. force by Native Americans. Afterwards, Congress voted funds for two new forts along the Yellowstone River, authorized 2,500 new recruits to be sent to Sioux country, and moved control over reservations from the Indian Bureau into the hands of the U.S. Army.

In August, Congress passed the Sioux Appropriation Bill stating that “hereafter there shall be no appropriation made for the subsistence” of the Sioux, unless they first relinquished their rights to the hunting grounds outside the reservation and ceded the Black Hills to the United States. Red Cloud's Oglala band signed, after which all of his followers were disarmed and dehorsed, but once again, the requisite two-thirds of all males required by the last treaty, did not sign.

1877 Congressional Act of 1877 violated the Fort Laramie Treaty by requiring the Sioux to relinquish the Black Hills and 22.8 million acres of their surrounding territory. In less than 20 years, the Sioux Nation shrunk from 134 million acres to less than 15 million.

1889 After the Sioux refused to sell 9 million additional acres of their reservation to the US government, Congress passed the Sioux Act. The Act redefined the requested 9 million acres as "surplus lands" open to white settlement under the Dawes Act and divided the Lakotas into five separate reservations: Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, and Upper and Lower Brule. The remaining land was given to the new states of North and South Dakota. Any Indians who refused to be confined to reservations were declared "hostile." The 9 million acres was then opened up for public purchase for white ranchers and homesteaders.

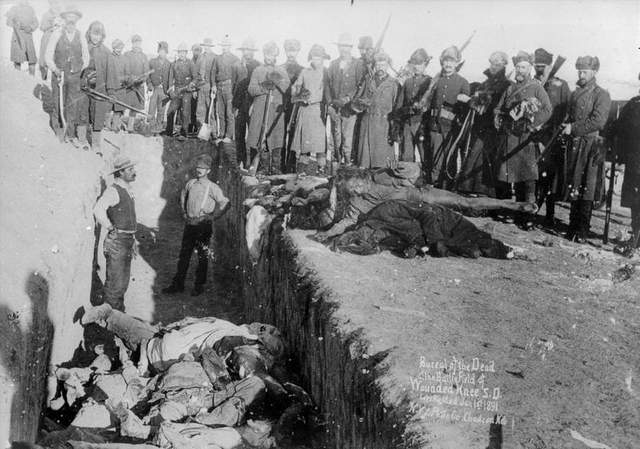

On December 29, 1890, Sioux Chief Big Foot met four cavalry units which were under orders to capture him. The Sioux raised a white flag to signal their promise not to fight. They were taken to an army camp at Wounded Knee Creek where they were ordered to give up their weapons. The medicine man, Yellow Bird, started the Ghost Dance, urging his tribesmen to join him by chanting in Sioux, "The bullets will not go toward you." When one young Indian refused to give up his rifle, confusion ensued during which several braves pulled rifles from their blankets, and the soldiers opened fire. At least 150 Indian men, women, and children were left dead; as many as 300 may have perished when the wounded died soon thereafter. The Seventh Calvary, Custer's avenged regiment, received 23 Congressional medals of honor for their involvement at Wounded Knee—the most ever awarded for a single “battle”.

1896 On February 22, 1897, President Grover Cleveland established the Black Hills Forest Reserve. This land was protected against fires, wasteful lumbering practices, and timber fraud. In 1905, the Black Hills Forest Reserve was transferred to the Forest Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In 1907, it was renamed the Black Hills National Forest.

1910 The Sioux Reservation was further reduced with the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations losing more land to white homesteaders.

1923 The Lakota Sioux filed suit with the US Court of Claims demanding compensation for the loss of the Black Hills. It was not until 1942 that the Court finally dismissed the claim.

1946 The Sioux filed suit with the newly-created Indian Claims Commission. In 1954, the Commission dismissed the case on the grounds that it had already been denied.

1956 Sioux reinstated their claim to the Indian Claims Commission on the grounds that they had been represented by "inadequate counsel."

1973 The American Indian Movement (AIM) began the first organized extralegal battle for the Black Hills. AIM occupied Wounded Knee Cemetery on Pine Ridge Reservation to alert the world about the vested economic interest the U.S. government held in the Hills and the extent to which that interest governed U.S. governmental policy and federal court cases regarding their land. (For a detailed understanding of the upheaval at the Pine Ridge Reservation between 1973 and 1975, as well as the aftermath, click here.)

1978 Congress passed an act enabling the Court of Claims to rehear the case. Sioux argued that they should be compensated on new grounds - "dishonorable dealings."

1979 The U.S. Court of Claims found that the 1877 Act that seized the Black Hills from the Sioux violated the 5th Amendment. The US had taken the Black Hills unconstitutionally and court reinstated the $17.5 million plus 5% interest for a total of $105 million. The US government appealed.

1980 In the United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, the US Supreme Court found that the Congressional Act of 1877 constituted "a taking of tribal property which had been set aside by the treaty of Fort Laramie for the Sioux's exclusive occupation." The $105 million award was upheld. The Sioux then turned down the money, claimed that "The Black Hills are not for sale." Instead, they demanded that the US government return the Black Hills and pay the money as compensation for the billions of dollars in wealth that had been extracted and the damages down while whites illegally occupied the Hills.

1983 The Black Hills Steering Committee was created and its members drafted a bill for Congress that asked for 7,300,000 acres of federal land in the Black Hills in South Dakota. The Committee promised to keep all federal employees working in the Black Hills.

1985 U.S. District Court Judge ruled in favor of AIM, arguing that the Lakota had every right to the Yellow Thunder Camp (shown at the right), particularly because AIRFA recognized entire geographic areas as well as specific sites to be sacred areas.

1988 The Eighth Circuit Court reversed the U.S. District Court's decision. AIM ended its occupation of Yellow Thunder Camp.

2000 The U.S. Supreme Court denied the plaintiff's appeal of the 10th Circuit ruling, thus upholding the appellate court’s decision as final. Nonetheless, climbing was allowed to resume. However, National Park Policy requires that during June, rangers ask climbers to voluntarily refrain from climbing on the Tower and hikers to voluntarily refrain from scrambling within the inside of the Tower Trail Loop

2007 On December 19, a small group of activists calling itself the Lakotah Freedom Delegation announced that the Lakotah were withdrawing from all treaties previously signed with the United States and were planning to regain their sovereignty over thousands of acres of traditional territory in North and South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska and Montana. According to the group, the withdrawal immediately and irrevocably ended all agreements between the Lakota Sioux Nation of Indians and the United States Government outlined in the 1851 and 1868 Treaties at Fort Laramie Wyoming. The group argued that their declaration of independence was not a secession from the United States, but rather a reassertion of sovereignty. Their leader was Russell Means, one of the prominent members of the American Indian Movement in the late 1960's and 1970's.

Property ownership in the five-state area of Lakota nation - parts of North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming and Montana - had been illegally homesteaded. Lakota representatives announced that if the United States did not enter into immediate diplomatic negotiations, liens would be filed on real estate transactions in the five state region, clouding title over literally thousands of square miles of land and property.

2012 The monetary compensation gained through the longest legal battle in U.S. history remained unclaimed; the settlement is now worth about $1 billion. The map to the left shows the original land promised by the 1868 treaty (gold), the land - including the Black Hills - illegally taken by the U.S. government in the 1877 (orange), and the Lakota reservations as they appeared after 100 years of court actions (brown).

Pine Ridge Reservation, home to many of the Lakota people, is one of the poorest communities in the United States.

NoDAPL Movement

2015 – Oct 2016 A bizarre timeline of supposed outreach to the Standing Rock Tribe by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) that is like some disrespectful pantomime in slow motion. Then follows one intrusion after another onto the unceded and still disputed lands that were lawfully signed over to the Great Sioux Nation in 1851.

Nov-Dec 2016 An escalation of violence against Indigenous water protectors and their allies of every race and many nations raised to such heights that the media blackout finally broke. On December 4th more than 2,000 US Veterans deployed to help act as human shields to defend Americans and “ . . . support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic”, in this case, militarized law enforcement were the enemies. Then on the same day, the ACE finally denied DAPL the easement they required to drill under the Missouri River, seemingly ending the conflict. It seems the Obama Administration finally came through. But the plan to do an environmental impact study and see if they can “reroute” the pipeline does not mean the war is over.

Conclusion: As Bernie Sanders pointed out in an interview with DemocracyNow, there is a three-fold problem with this pipeline.

“Number one, we’re dealing with sovereignty rights for Native American people, an invasion of their own property, in violation of treaty rights, which is an endemic problem in this country. Number two, you’re talking about an area where, if the pipe bursts, water, clean water that goes to millions of people in that region, could be severely impacted, at a time when we’re all concerned about the amount of clean water that we have. And thirdly, and most importantly perhaps, you’re talking about whether or not we should be in any way supporting a pipeline which is piping in filthy oil at a time when we need to transform our energy system away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy. So those are the three issues there.” - Senator Bernie Sanders

When the history is reviewed in detail, I’m struck by how much we are repeating ourselves. At Standing Rock, we have a combustible mix of local and out-of-state (and therefore out of jurisdiction) sheriff’s department officials (in disguise, with no visible identification) and private security personnel (who brought us such memorable hits as unlicensed attack dogs bite water protectors—all of whom seem to be heavily militarized. Peaceful protectors are constantly under the eyes of snipers and near constant helicopters that are reported to even fly in the dark in the middle of the night. Many believe this surveillance is a form of psychological warfare to prevent sleep and generally intimidate, as well as inhibit access to social media and even widespread privacy intrusion of protestor encampments.

Indigenous Americans have a right to the land they occupy and are simply trying to protect their water supply (and it’s worth noting, the water supply that 6 to 18 million American citizens depend on). The above history tells us all we need to know about why they don’t trust that the US government nor the kind of corporation that can invoke a militarized crackdown, have the tribe’s best interests at heart. The time is right for them to stand up again and be heard!

With breaking news that the pipeline will not go through on the disputed land, now is the time to answer the more important question: Who’s land is this really?

The evidence is clear. The court already ruled in the tribe’s favor in the United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, the US Supreme Court found that the Congressional Act of 1877 constituted "a taking of tribal property which had been set aside by the treaty of Fort Laramie for the Sioux's exclusive occupation."

The soul of America needs to reconcile its treatment of the first Americans, who only lost their lands for the crimes of not being immune to European diseases, not being genocidal, and occasionally trusting in the word of the white man. They could not conceive of the greed and dishonesty they would face. They couldn’t imagine wholesale slaughter of the buffalo or their own people, nor that man could cut and poison so much land and water.

We cannot go back and change the past. But we can listen to the pain of the past, trapped as it has been in a soundless, strangled cry. We can listen.

And we can give back the lands stipulated in the treaties signed to all the Tribes or else make fair compensation. We can stop treating the first Americans like problems that have to be managed (read: exploited) and instead give all the tribes a seat at the tables of government, the way we should have done since the time of treaties and land negotiations began.

Give back the Black Hills. It’s theirs by treaty, along with a 120+ million acres. Maybe not all can be given back, but use that first Fort Laramie treaty as a place to start negotiations. Federal and State lands within those borders should go back to the tribes in an equitable manner and some fair financial compensation should be met out for the vast mineral resources that were stolen from them in the last 150 years. This includes Army Corps of Engineer lands inside the 1851 boundaries.

America’s tribal societies lived here sustainably for thousands of years while those of European descent have managed to trash the place in a few hundred. We should not only make repairs, but look to the lessons and wisdom of the tribes that helped inspire our democracy as we renegotiate our own contract with America that includes all the human beings in a way that is sustainable. The other option is death and moral decay . . . which is not really an option.

Native America is not in a history book or a museum exhibit. It is not a tragedy tale to avoid, get depressed over, or elevate into nonsensical myth. It is alive—injured and set back—but alive and today it needs all of our support to repair the wounds of the past. Only then can we collaborate to solve the problems of today for the benefit of all the generations to come.

Now is the time.

Honor the Treaties!

Crazy Horse Prophecy:

"Upon suffering beyond suffering, the red nation shall rise again

and it shall be a blessing for the sick world.

A world filled with broken promises, selfishness and separations.

A world longing for light again.

I see a time of seven generations, when all the colors of mankind

will gather under the sacred tree of life

and the whole earth will become one circle again.

In that day, those among the Lakota who will carry knowledge

and understanding of unity among all living things,

and the young white ones will come, to those of my people to ask for wisdom.

I salute the light within their eyes where the whole universe dwells,

for when you are at the center within you

and I am at that place within me, we are as one."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed